Of Scimitars and Shakespeare

The scimitar was among the most obvious non-Christian symbols used in early modern English drama. Associated not just with Turks or Islam, it became a symbol of the feared aggression of the exotic East. Flashing as a symbol of threat, bravado and cultural otherness, the scimitar makes rare but striking appearances in Shakespeare’s plays.

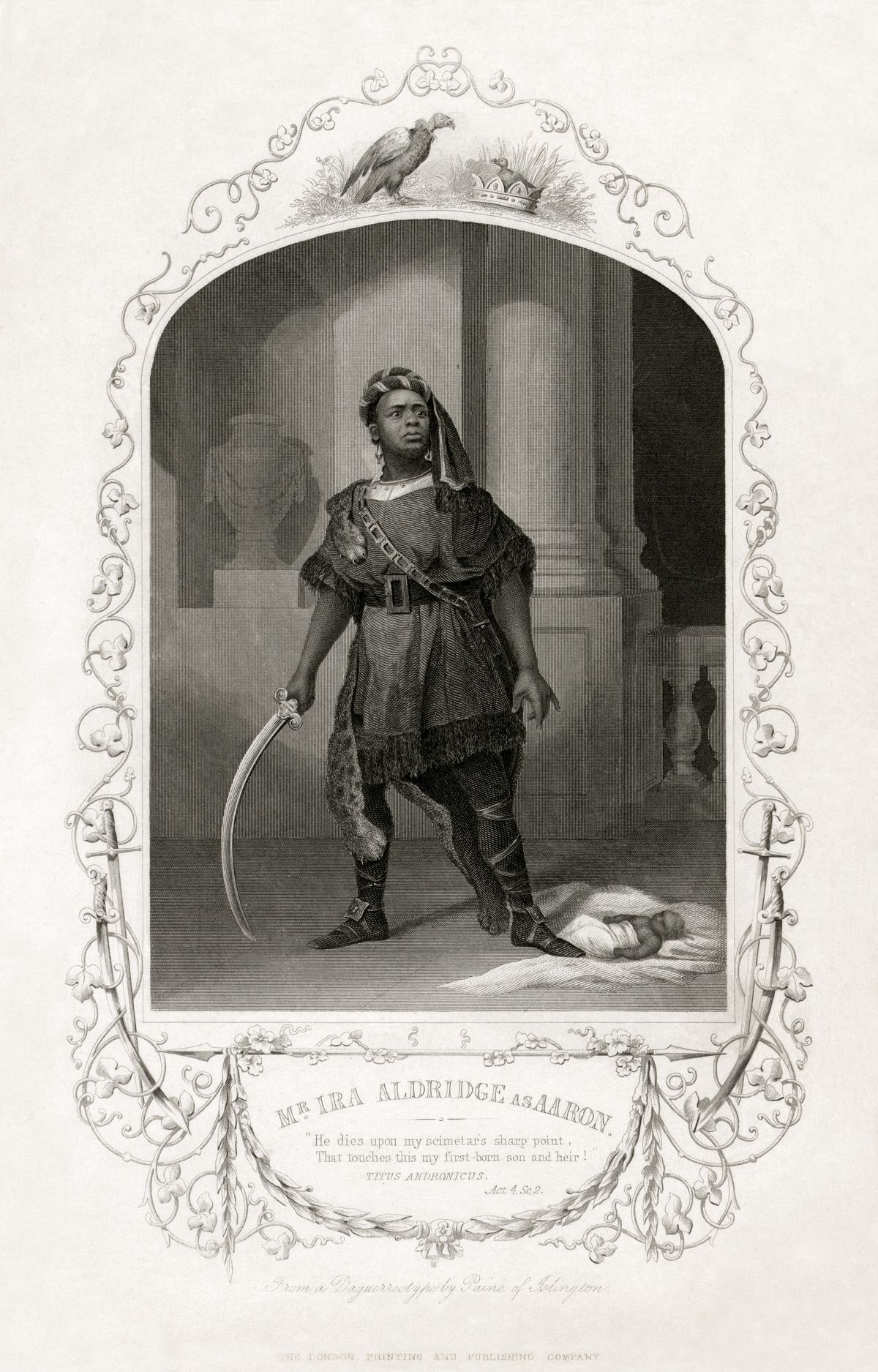

In Titus Andronicus, for instance, the villainous Aaron the Moor draws his scimitar to defend himself against Tamora’s sons, who threaten him and his infant son:

Now, by the burning tapers of the sky,

That shone so brightly when this boy was got,

He dies upon my scimitar’s sharp point

That touches this my firstborn son and heir! (4.2.91-94)

Aaron’s racial otherness, underscored through the blackface used by the early modern actor, is accentuated with the scimitar as a theatrical prop, further highlighting his Moorishness through his Moorish weapon.

Ira Aldridge as Aaron. Library of Congress (Public Domain). Image via Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, in The Merchant of Venice, the Prince of Morocco’s swaggering courting of Portia is as exaggerated as, possibly, the size and the provenance of his scimitar:

By this scimitar

That slew the Sophy and a Persian prince,

That won three fields of Sultan Solyman [...] (2.1.24-26)

Martial prowess is used to impress Portia, not simply by highlighting his social status, but also by insinuating the Prince of Morocco’s strength as a lover, implying a sexual innuendo in the phallic scimitar. The equation of the scimitar as a symbol of Islamic aggression threatening Christians through the Prince’s machismo, through which he tries to win over the Christian maiden Portia, is not simply a comic scene intended for laughter, but also visualises interracial anxieties in early modern England.

Scott Karim as Prince of Morocco in The Merchant of Venice, directed by Jonathan Munby (2016)

Image via Jonathanmunby.squarespace.com

Yet, it is interesting that it is not only Muslims/Moors who are racially profiled through the scimitar, but also Greeks in Troilus and Cressida. In the play, the Greek warrior Achilles contemplates before a feast his subsequent murder of Hector:

I’ll heat his blood with Greekish wine to-night,

Which with my scimitar I’ll cool to-morrow. (5.1.1-2)

The presence of the scimitar is not merely another anachronism in the play (see Evrim Doğan Adanur), but underscores how Shakespeare portrays most of the Greeks in the play as antithetical to heroic ideals. Thus, the scimitar symbolises anti-Christian, anti-West, and anti-English sentiments that are made visible through this non-English sword.

Shakespeare, as an early modern English playwright, deploys the scimitar sparingly but deliberately as a marker of Eastern otherness and the anxieties associated with it across time and space, which his characters use for defiance, swagger, and splendour.

Murat Öğütcü

Select Bibliography

Dimmock, Matthew. “Materialising Islam on the Early Modern English Stage.” Early Modern Encounters with the Islamic East: Performing Cultures. Edited by Sabine Schülting, Sabine Lucia Müller, and Ralf Hertel. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012, 115–34.

Doğan Adanur, Evrim. “The Uses of Anachronism in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida.” Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences 16.4 (2017): 1048-1056.

Shakespeare, William. The Merchant of Venice. Edited by John Drakakis. London: Arden Shakespeare, 2011.

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. Edited by Jonathan Bate. London: Arden Shakespeare, 1995.

Shakespeare, William. Troilus and Cressida. Edited by David Bevington. London: Arden Shakespeare, 1998.