Picturing Muslims: Nicholas Nicholay’s Muslim Women

Today’s post is the second in a series of blogs where I explore some of the well-known representations of Muslims that appear in early modern European and English visual culture, and consider how these images may have influenced or been influenced by the way Muslims were conceived, both in character and physical form, in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. You can read my first post on Bellini’s portrait of Sultan Mehmet I here.

During the periods when dramatic productions about Muslims were in vogue in early modern England, playwrights did not only create fearsome, tyrannical Turkish male characters but also a wide range of interesting female Muslim characters who, like their male counterparts, reflected England’s mixed views on the Muslim world. Some of these figures, like Marlowe’s Arabian Zenocrate and Turkish Zebina (Tamburlaine I, 1587), or Heywood’s Moroccan Tota (Fair Maid of the West II, 1631), are women of noble ranking whose shared ambitions with their power-hungry husbands mark them as equally admirable and threatening. Other esteemed princesses, like Massinger’s Tunisian Donusa (The Renegado, 1624) and Fletcher’s Indonesian Quisara (The Island Princess, 1621), were perceived as sexually desirable but also spiritually ‘redeemable’ and thus able to be integrated into European society in a way that challenged ideas around Muslim differences. By contrast, figures of relatively lower social positions, such as Daborne’s Voada (A Christian Turned Turk, 1612) and Field, Fletcher, and Massinger’s Zanthia (The Knight of Malta, 1618), were ascribed with qualities of promiscuity and villainy, which highlighted the gendered immorality, religious evil, and racial difference that were central to English beliefs about Islamic or Muslim degeneracy.

The extensive number of female Muslim characters that featured on stage suggests that playwrights and theatre companies needed to have had an effective set of visual codes for presenting these disparately characterised women on stage, and that early modern audiences would have been able to read these receptively. Today’s post explores one of the texts circulating in early modern Europe that may have offered visual inspiration to the English theatre practitioners trying to perform these women on stage, as well as, more generally, influenced how the English pictured women from the Muslim world.

Muslim Women in Nicholas Nicholay’s The Navigations, Peregrinations and Voyages made into Turkie (1585)

Nicholas de Nicholay was a sixteenth century French geographer and writer (and some say a state spy). In 1551, King Henri II of France sent Nicholay on a diplomatic excursion to the Ottoman Empire, which was then ruled by Sultan Suleiman I or Suleiman the Magnificent. The journey was motivated by Henri’s attempt to continue to cultivate the productive geopolitical alliance between France and the Ottomans that had existed between Suleiman I and Henri’s predecessor, Francis I. Nicholay’s Les Quatre Premiers Livres des Navigations et Peregrinations Orientales (1567) – a detailed account of the customs related to the groups, institutions, and geographies within the Ottoman domains – was an outcome of his ambassadorial visit.

Les Quatre Premiers includes discussions on, amongst other topics, organisational structures such as the government, the military, the economy, and the royal court; religious practices and customs, especially Islam; cultural traditions and contemporary fashions; geography, terrain, fauna and flora; as well as everyday practices around service, hygiene, family dynamics and the marketplace. Given the expansive overview it lays out of life in the powerful and dynamic Ottoman world, it is no surprise that the text was disseminated throughout various parts of Europe, including Italy, Germany, and England. T. Washington the Younger’s English translation of the work was published in London in 1585 as The Nauigations, Peregrinations and Voyages, made into Turkie by Nicholas Nicholay Daulphinois, Lord of Arfeuile.

Featured alongside the writings in The Navigations are “figures, naturally set forth as well of men as women, according to the diuersitie of nations, their port, intreatie, apparrell, lawes, religion and maner of liuing”.[1]Nicholay had drawn his own sketches while on his travels through the Ottoman domains, and these were later reproduced by Louis Daret for an edition of the book published in Antwerp in 1567. The illustrations which appear in the English translation were copied from Daret’s drawings, and follow in the traditional style of Renaissance costume books, with detailed full-length portraits of figures accompanied by short captions. Thus while not an exact replication of Nicholay’s own images, the drawings which were being shared around England more or less represented figures as they were originally conceived by the Frenchman.

The images of women included in the edition would have been particularly intriguing to English readers, who more frequently encountered descriptions of the ‘Great Turk’ or ‘Barbarous Moors’ in political and religious texts without a corresponding view of Muslim women. Nicholay’s illustrations of women would have necessarily provided the English with a sense of the plurality of the Ottoman Empire, the social demographics of the Muslim world in general, as well as the quotidian practices of the women inhabiting it.

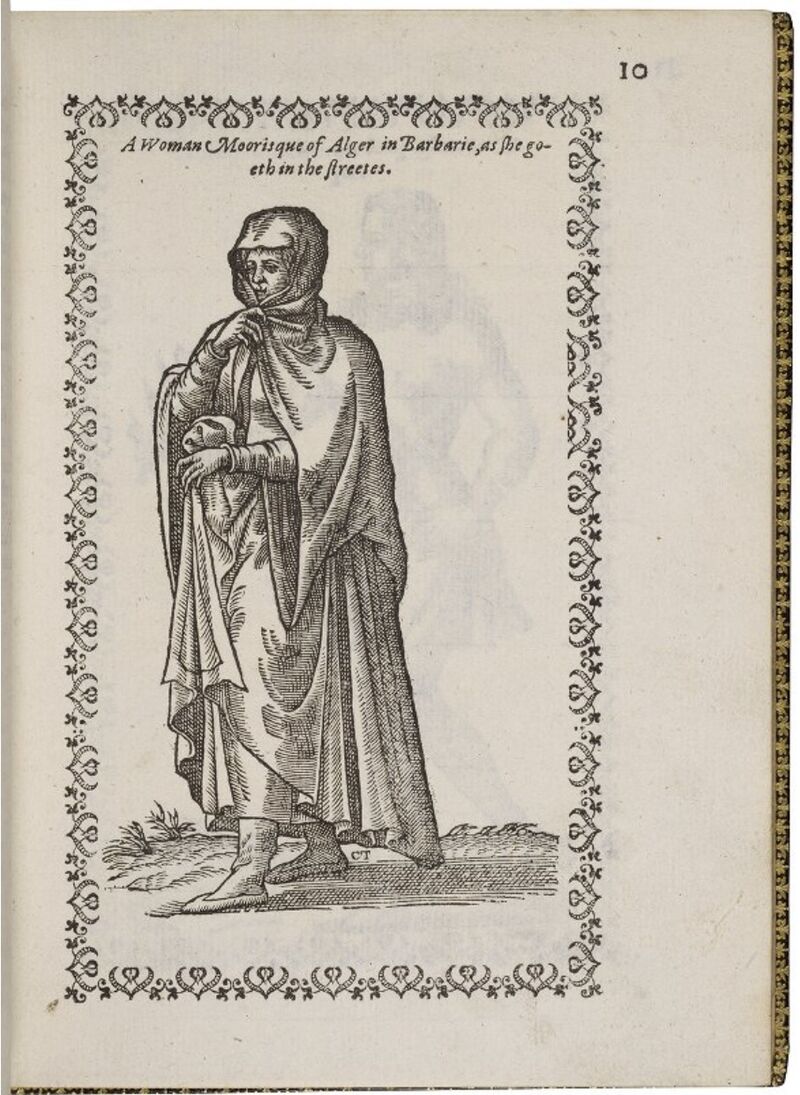

For example, Nicholay shows images of “a Woman Moorisque of Alger in Barbarie” (p.10) as they “goeth through the streets” (p.10), and similarly “Woman Turk going to the Bathe” (I1r, p. 61) or “through the Citie” (I3r, p. 63). Women from different socioeconomic groups are also depicted, like the “Mayden Moorisque” (p. 11) who is a “being a slave in Alger” (p. 11) or the “Gentlewoman of the Turks being within her house or Sarail” (p. 54). Notably, clothing becomes a means of characterising sameness and distinction between these women. The Moorish “slave”, for example, is drawn almost entirely without clothing, while the Turkish gentlewoman appears in highly decorated clothing with high heeled shoes and distinctive hair pieces. At the same time, the Turkish and Moorish women walking through their respective cities are portrayed consistently, being attired in full-length, drapey dresses and with hijabs or veils that cover all their hair and significant parts of their faces.

Figure 1: ‘Woman Turke going through the Citie’ in Nicholas Nicholay, The Navigations (London: 1585), I3r (p. 63). [Image Source: Folger Shakespeare Library, LUNA]

Figure 2: The above image from the 1577 Italian translation of Nicholay’s text, Le navigationi et viaggi nella Turchia, shows a “Gentildonna Turca Stando in casa ò in Serraglio”, which translates as a ‘Turkish Gentlewoman staying at home or in Serraglio’. Though the English translation of the text does not include images with equally wide colour palettes, this Italian copy nonetheless gives us a view of some of the colourful fabrics and dynamic styles of fashion emerging from the Ottoman Empire. [Image Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University via Wikimedia]

Figure 3: A Woman of Turke going to the Bathe in Nicholas Nicholay, The Navigations (London: 1585), I1r (p. 61). Discussing women’s hygiene and their use of Turkish baths, Nicholay observes, “these baths are so accustomably frequēted of the Turks, & that likewise the womē of estate do so gladly go thither in the morning betimes for to remain there vntil dinner time, beyng accompanied with 1. or 2. slaues, the one bearing on her head a vessel of brasse made after the fashiō of a smal bucket to draw water with, and within the same is a fine & long smock of cotton tissed, besides another smock, breeches, & other like linnen”. The image above presents a wealthy woman on her way to the bath with a “slave”(H4v, p.60). [Image Source: Folger Shakespeare Library, LUNA]

Figure 4:‘A Woman Moorisque of Algier in Barbarie, as she goeth in the Streetes’ in Nicholas Nicholay, The Navigations (London: 1585), B6r (p.10) [Image Source: Folger Shakespeare Library, LUNA]

Nicholay’s prefacing of his drawing throughout the text conveys some indication of how the writer rendered his profiles of these figures. The writer frequently refers to drawings in the collections as being “natural” or “naturally” sketched which implies an empirical accuracy about the images. At the same time however, Nicholay also suggests that some of his figures have been ‘staged’ for the purposes of the edition. For instance, the Navigations includes an image of “A Woman of Persia” that follows a descriptions of “Persians” who “in their habite goe very honourably clothed and like vntoo the Turkes and Grecians weare long gownes, closed and buttoned before, and attyre their heads with sundry bandes of diuers colours, the endes whereof hang downe verye lowe before and behinde ouer their shoulders” (Q4r, p. 119). Nicholay expounds that “the picture following doth shew vnto you", the reader, “the fourme and maner as which I haue naturally drawen out in Constantinople, with the fauor of a Persian with whom I was entred in friendship” (Q4r, p.119).

Figure 5: ‘A Woman of Persia’ in Nicholas Nicholay, The Navigations (London: 1585), Q4r (p.119) [Image Source: The Huntington Library via EEBO]

His descriptions also occasionally reveal that Nicholay imagined the drawings as sites for interpreting the features and cultures of the Muslim world. In his account of an “Azamoglan Rustique” (the Christian children converted to Islam and brought into Ottoman service via the tribute tax system), for instance, Nicholay suggests that in the accompanying image there “may almost bee seene and iudged, their gesture and great manhood” (X3v). The writer’s supplementary caption here, which guides the reader to identify the Christian subjects of the Ottoman world with “greatness” and masculine virtue, shows that Nicholay recognises the potential for these graphics to be regarded not simply as documentary drawings, but also as visual objects from which social and cultural judgements about Muslim society might be made.

Thus Nicholay’s drawings offered the early modern English insights into the visual appearances and clothing customs of Muslim women living in and around the Ottoman Empire as well as those in neighbouring regions. At the same time, as Nicholay himself implies, these visual impressions were also able to establish conceptual impressions and therefore shape early modern European and English cultural views on Muslims.

Further Reading:

If you’d like to learn more about these images from Nicholay’s text, and visual representations of Muslim women in early modern Europe, here are some works that may be of interest to you:

Andrea, Bernadette, The Lives of Girls and Women from the Islamic world in Early Modern British Literature and Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017).

Madar, Heather, ‘Before the odalisque: Renaissance representations of elite Ottoman women’, Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6(2011), pp. 1-41.

Wunder, Amanda, ‘Western Travelers, Eastern Antiquities, and the Image of the Turk in Early Modern Europe’, Journal of Early Modern History, 7(2003), pp. 89-119.

References:

Lue, Leslie ‘Documenting the Invisible: European Images of Ottoman Women, 1567-1867’, The Print Collector’s Newsletter, 1(1993), pp.1-3.

Nicholay, Nicholas, The Navigations, Pereginations and Voyages made into Turkey (London: 1585).

[1]Nicholas Nicholay, The Navigations (London: 1585), front page. All further page references to this work are given in the body of this post. Because there are different citation practices used to reference the page numbers in publications on Nicholay’s text, I include both page numbers and signatures where both are identifiable, and where one is more obviously marked and cited than the other I include only the more apparent form of the two references.