The Rose Galley Incident

On Thursday 13th November 1735, the Rose Galley, an East India Company ship, arrived in Bandar Abbas after a voyage to the coast of Sind. The galley had been dispatched with an unusual mission, for rather than carrying trade goods for sale in the Persian port, the Rose Galley had a more solemn cargo; the effects of a dead Persian ambassador, Mahmud Ali Khan, who had been despatched to the court of the Mughal Emperor, Muhammad Shah. The local boatmen, who transported cargoes from ship to shore, were reluctant to handle these items, not so much out of a respect or fear of its departed owner but owing to the fact that something else was missing. The Rose Galley was meant not only to carry the late ambassador, but also to be returning his two successors, Safi Khan Beg and Mahmud Sayed Beg- but they were nowhere to be seen. John Harris, the captain of the Rose Galley, reported that these two, along with their retinues had been left behind on the desolate coast of Sind having “grossly abused” and thrown “abusive affronts” at the scandalised crew of the Company’s ship. According to Harris, the Persians had interfered with the resupplying of his ship with wood and water, commandeering local boats and porters who had been hired for this purpose and forcing them instead to deal with the embassy’s suite first. This caused some of the Company’s goods to be spoiled, having been left too long in the heat and sun, while also endangering the crew and their Persian passengers by leaving water to spoil. The sailors onboard became more and more mutinous at this treatment, forcing Harris and his officers to consider their position and that of the Company as their employers. All the while, Safi Khan Beg had refused utterly to leave his horses, despite being informed that they could not be taken onboard ship. Seeing his chance at a clean break, Harris used this opportunity to take Safi Khan Beg at his word, leaving him, his men and the horses stranded on the dock.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this caused some considerable consternation. The Company’s Agent, William Cockell, immediately began working to control the reputational damage that Harris’ actions could cause. At this time, the Company were in a precarious position in Persia, struggling to maintain a good relationship with Persia’s new de facto ruler, Nader Shah and the regional governor, Mohammad Taqi Khan Shirazi. These difficulties were compounded when the two marooned ambassadors arrived in port aboard a flotilla of coastal craft that they had hired. Naturally, they were furious. Harris was confined to his ship by Cockell, who then went on a charm offensive, using his already good working relationship with the Persian admiral, Latif Khan. Cockell was helped, perhaps unwittingly, by Safi Khan Beg himself, who reported to Latif Khan that he had feared being thrown overboard by the sailors and was saved only by the intervention of Harris and the ship’s Mates. Cockell, picking up on this theme, is reported to have said “…our seafaring men’s behaviour is generally as boisterous as the element they have to deal with…” and saying that he and his fellow merchants too often found their deportment lacking in social graces. Cockell’s soothing, along with a payment of nearly 20,000 shahis to the ambassadors to cover the hiring of the local boats, as well as a consideration for their personal discomforts, did the trick. Indeed, so satisfied were the ambassadors with this conclusion, that they happily signed a letter addressed to Nader Shah himself stating how well they’d been treated.

These events, like so many in the archive, show us a great deal about the complexities of day-to-day life, whether for the Company’s merchants, the Persian ambassadors, or the crew of the Rose Galley and its captain. Particularly of interest here is the often-unrecognised influence of the enlisted men aboard the Company’s ships. The reports of Safi Khan Beg and Harris attest to the way the men’s’ attitudes and reactions to their Persian passengers could have resulted in a far more serious diplomatic spat. Captain Harris’ actions likewise give a glimpse of his priorities, and how his risky decision to abandon his Persian charges might well have saved their lives, or at least an undignified soaking. Finally, the response of Cockell shows a nuanced understanding of the interests of his Persian interlocutors, skilfully managing a volatile situation with diplomacy, taking advantage of his existing relationship with Latif Khan and, indeed, parting with a fair weight of silver. The results, however, were probably worth the pain for Cockell, for he maintained Latif Khan’s good ordinances and used the letter signed by the ambassadors to secure some much-needed stability in the Company’s trade.

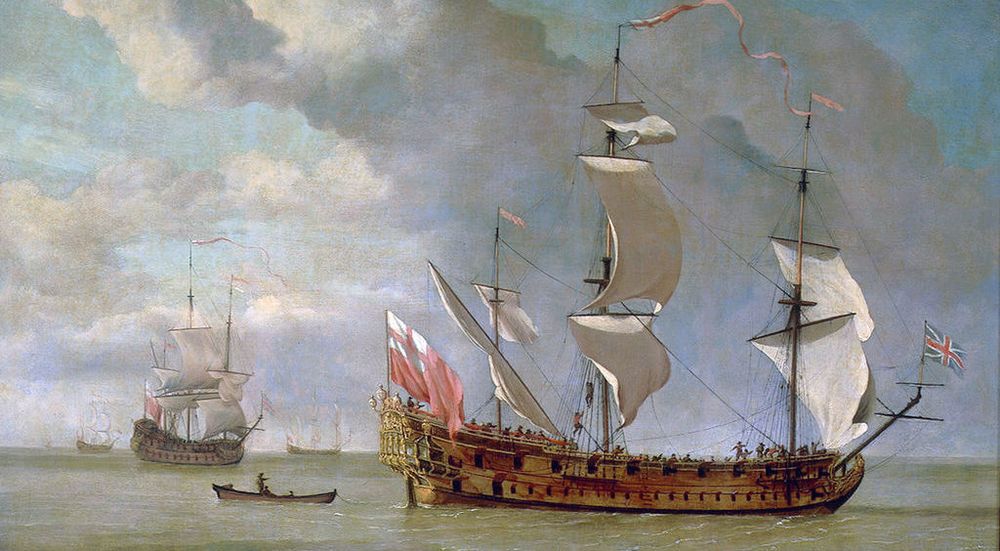

Title Image: HMS Charles Galley by Willem van de Velde the Younger, accessed here