Reading the Maghreb in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Part 2: Networks of Readership

This post continues my ongoing work in marginalia and provenance in early modern books about the Maghreb printed in Britain. The first post on this topic is ‘Reading the Maghreb in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Speculative Investigation’. While reading what was written and published is one way into understanding the public’s perceptions, I would argue that much scholarship on the reception of the Maghreb subtly conflates the content of texts and the reception of texts. Kenneth Parker asks ‘What did English readers know about the Maghreb and by which means did they acquire that knowledge?’, Daniel Vitkus talks about ‘anxious interest’ in popular literature and plays, and Laurie Ellinghausen sees a slew of emotional responses to British converts to Islam – but in all cases, it is writers rather than readers that they examine.[1] Seeking to understand not only what resources were available, but how they were being read, this project investigates the provenance and marginalia of some 6,600 copies of 680 titles related to the Maghreb printed in early modern Britain, preserved in libraries across the world. This survey is a little unconventional in marginalia studies, which usually focus on the marginalia found in copies of a single title or in the library of a specific reader, rather than coverage of a particular region of the world. In my first post, I highlighted some examples of marginalia; in this post, I will discuss early results from my investigations of provenance.

Due to the prevalence of marks indicating ownership, books are one of the few material items from the past that can be with certainty connected with a particular owner. Marks of ownership offer a ‘money-where-your-mouth-is’ commitment to interest in a book or connection to a community of interest, and dates connect books to eras where they were read.[2] As a kind of pilot study for this project, I undertook a systematic survey of 22 titles published in the 1670s, held in 169 different libraries around the world. This was a period when the Maghreb was attracting new kinds of attention across a range of genres, as new peace treaties started to regulate and normalise British-Maghrebi relations, and new sources of information like newspapers were bringing a new kind of encounter with knowledge about the Maghreb.

Figure 1: The frontispiece of William Okeley, Eben-Ezer: or, A Small Monument of Great Mercy (London, 1675). Huntington Library 132353, photograph by the author.

Excluding one-off news-sheets and newspapers, which were rarely marked, the 1670s saw the publication of John Ogilby’s hefty geography Africa; two books from Oxford-educated chaplain Lancelot Addison, West Barbary and The Present State of the Jews, which offer an early-Enlightenment intellectual approach to contemporary Moroccan history and Moroccan Jewish customs based on his time in English-occupied Tangier; two political, economic, military and social accounts written by first-hand witnesses in George Phillips’ Present State of Tangier and Samuel Martin’s Present State of Algiers; plays including Aphra Behn’s Abdelazer, Elkanah Settle’s Empress of Morocco, and John Dryden’s Conquest of Granada, alongside Dryden’s published argument with Settle about how terrible the Empress was, and a burlesque parody of the Empress; plus two novels, two travel accounts, and three captivity narratives written by Europeans enslaved by Maghrebi corsairs (Figure 1). Among these titles, there were 616 surviving copies across 169 libraries around the world. Some had many more copies than others, and many had no catalogued marks, but nevertheless I identified 113 volumes which had one or more named early modern owners.

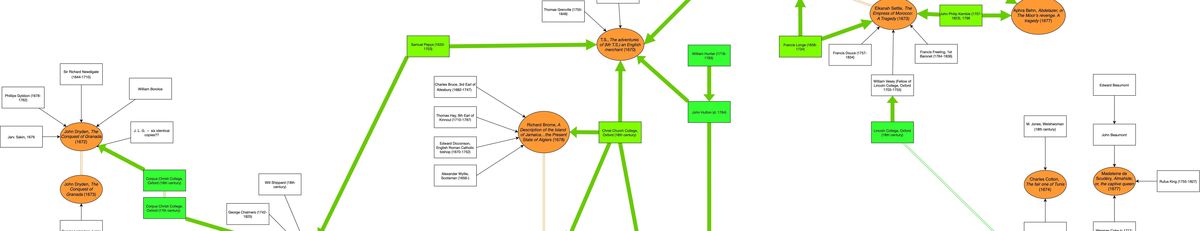

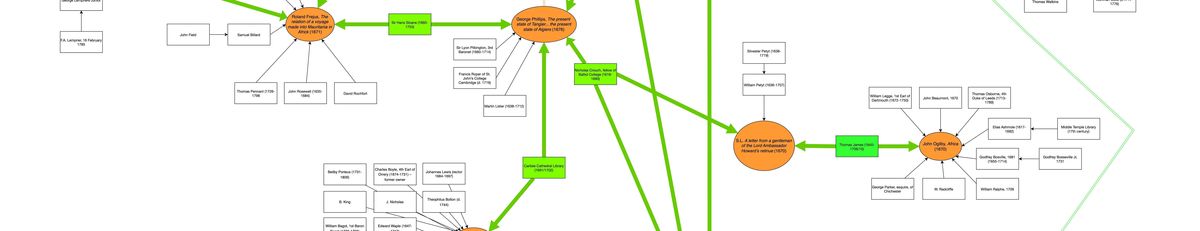

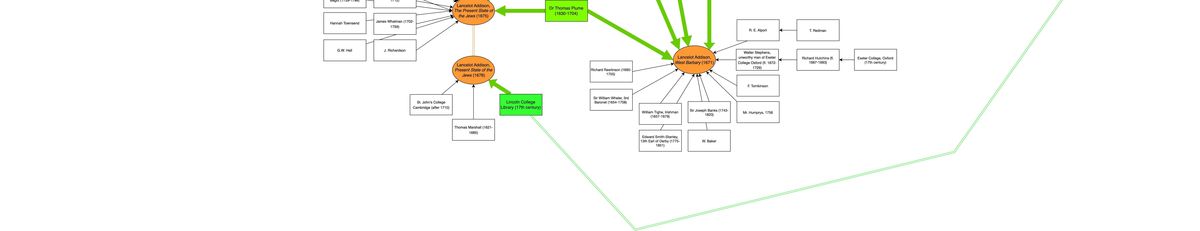

With apologies to any digital humanists reading this post, here’s a first version of the network of ownership that results (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Experimental network diagram of ownership of books about the Maghreb printed in Britain, 1670-79. To view a higher resolution version, click the link: (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZZ98eV8PW-wicE1_xrVYfbM-rfNoc4k2/view?usp=sharing)

The titles, in orange circles, are connected to their readers in white squares, and those who owned multiple titles are flagged in green. I made orange connections between texts when there are repeat editions or direct reactions to one another, and connections between readers when the same copy passed between them. If we pick apart this complicated and very preliminary diagram, a number of interesting insights emerge.

At a quantitative network analysis level, the works of Lancelot Addison (bottom-centre) have the highest ‘degree centrality’, with connections to over 30 readers between the three of them. A volume combining a contemporary account of the English colony of Tangier (occupied 1662-1684) and Ottoman Algiers (centre) was a crossover hit, ‘betweenness centrality’, connecting with readers of Addison’s works, captivity narratives, and travel accounts. Another hit, as was the raunchy Algerian captivity story Adventures of Mr T.S. (top-centre) which also connects to this larger, close-knit section of literary works featuring Settle’s Empress of Morocco and its burlesque parody, Dryden and Settle’s argument, and Aphra Behn’s Abdelazer (top-right), though not, interestingly, Dryden’s Conquest (top-left). Since T.S. is suspected to be heavily fictionalised, it might be a reasonable bridge to this most literary cluster, interconnected by literary collectors like the contemporary Francis Longe (1658-1734) and later eighteenth-century libraries of John Phillip Kemble (1757-1823) and Edmund Malone (1741-1812). Dryden and Settle’s published spats are linked by Narcissus Luttrell, who styled himself a political journalist, and to that end purchased hundreds of contemporary pamphlets including a range of other very short texts about the Maghreb not included here. Just below them (centre-right) are two titles, both novels, with no common owners: Charles Cotton’s The Fair One of Tunis, and Almahide by Madeleine de Scudery.

On this evidence, there are numerous owners whose view of the Maghreb as presented in seventeenth-century texts might have been shaped only by fiction, and others only by a particular non-fiction volume, but there were other readers who wanted to read multiple genres of books, triangulating multiple witnesses to get a more detailed insight about the Maghreb. Some of the most prolific ‘owners’ listed here are larger institutional and family libraries, including Bridgwater House, Carlisle Cathedral, and several Oxford colleges, which were built over time by various people and thus cannot be easily tied to particular readers, even when the provenance is clearly early modern and where numerous other readers might have encountered the book without leaving a trace.

If, for the sake of specificity, we exclude these, the network looks a little more fragmented, but a couple of bridging readers are worth noting. In the top-left is Samuel Pepys, of 1660s diary fame. Pepys worked in the Admiralty, which headed up conflicts with Algiers and Tripoli through the 1670s, and he was personally involved in the evacuation of English Tangier in 1684, so he was in a position to know quite a lot about the Maghreb without buying any books. Buying Roland Frejus’s account of a voyage to southern Morocco, far from Tangier, might have been designed to fill gaps in his knowledge, and T.S.’s story is just saucy enough to suggest that philandering Pepys read it for fun, though perhaps he absorbed some of the detailed engagements with Algerian fiscal-military organisation that T.S. includes along the way.

Linking Frejus and the Present State of Tangier…Algiers is Hans Sloane (1660-1753), whose vast library included all kinds of travel and geographical accounts, and would have reached thousands of others after it became the core of the new British Museum Library at his death.

A third bridging reader is Nicholas Crouch, an Oxford don, whose ownership of Tangier-Algiers, an account of a diplomatic mission to the Emperor of Morocco which departed from Tangier, and Addison’s West Barbary, probably indicate a particular, perhaps patriotic, interest in the fate and surroundings of English Tangier. In each case, these bridging authors connect with books also held by other bridging authors, offering a tiny glimmer of what might eventually reveal a community of interest.

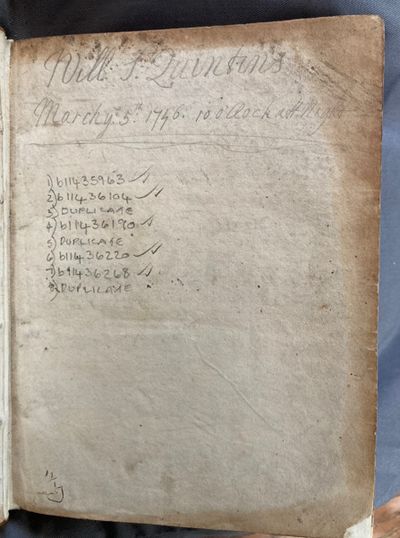

Each of these readers were near-contemporary, as were a number of others like Martin Lister, Elias Ashmole, and Thomas Pennant, the headmaster of Eton, and various members of the clergy, gentry and aristocracy, showing a widespread interest in current affairs and new analysis, but many books also had readers of similar professions right into the eighteenth century, suggesting that even the most contemporary factual texts were appreciated well after the time of writing. Some dated inscriptions are rather arresting, such as the night-time reading habits of William St. Quintin, 4th Baronet (1700-1700), ‘Will: S: Quintins, March ye 5th 1746, 10 o'Clock att Night’ on John Dryden’s scathing Notes and observations on the Empress of Morocco (1674) (Figure 3). Why Quinton should have thought it necessary to review critiques of a seventy-three year old play is a mystery, but this signature connects him to a community of readers, however distant, that extends across space and time.

Figure 3: The signature of William St Quintin, 4th Baronet, on John Dryden, Notes and observations on the Empress of Morocco (London, 1674). Trinity College, University of Cambridge, H.10.14.6[2]. Photograph by the author.

This preliminary investigation, as a microcosm of a much larger corpus, indicates a promising method, when combined with marginalia, for evaluating the prominence of books about the Maghreb in early modern English society, and what topics might be of interest to particular communities. I look forward to sharing more as I continue on!

[1] Kenneth Parker, ‘Reading “Barbary” in Early Modenr England, 1550-1685’, The Seventeenth Century 19 (2004): 87; Daniel Vitkus, ed., Three Turk plays from early modern England: Selimus, A Christian turned Turk, and The renegado (Columbia University Press, 1999), 3-4; Laurie Ellinghausen, Pirates, Traitors, and Apostates: Renegade Identities in Early Modern English Writing (University of Toronto Press, 2018).

[2] David Pearson, Provenance Research in Book History: A Handbook (Oak Knoll Press, 2019).